Marie Kristiansen’s “Moo” is a visceral, dynamic, and thought-provoking fashion film, designed to advertise a…

In Conny Karlsson Lundgren’s Koncert Në Vitin 2014, historical moments, both fictional and real, come together in a mausoleum rife with history. He films Lepurushja, a young queer Aleanca affiliate, reclaiming a traditionally conformative space as hir own and thus, becoming the voice of an unheard community. Here is our interview with this artist.

The title, Koncert Në Vitin 2014, refers back to Albanian filmmaker Saimir Kumbaro’s award-winning, yet internationally lesser-known film, Koncert Në Vitin 1936 (1978). Can you provide some background on the 1978 film? What critique does it propose of society?

Without simplifying Albania’s history too much, the country suffered from complete isolation for over 45 years after the second World War due to its communist regime and before that the Italian fascists occupied the country. During the communist era, over 270 feature films were produced within the state controlled film system Kinostudio Shqipëria e Re, which is quite impressive, considering the size of the country. The 1978 film Koncert Në Vitin 1936 (transl. Concert in the Year 1936) was inspired by the actual biography of the much loved Albanian soprano Tefta Tashko-Koço (1910–1947), who in the 1930s was touring the rural areas of Albania with her updated modern versions of traditional local folk songs performed in a more western-oriented song structure. The original film follows two women, a soprano and a pianist, in their struggles with the local authorities when they try to organize a concert in a small village. It’s a comedy and it was ingeniously disguised by being placed in 1936, because this was when the Albanian monarchy was supported by the fascist regime in Italy, but it’s very hard not to read into its sharp critique of the governing bureaucracy and heavy power structures of the 1970s communist era.

Did you attempt to make your film a contemporary version of the critique made in 1978? After so many years in between, what has changed and what has not?

The current LGBTQ movement in Albania is quite young and can be traced back to 2008. You can’t emphasize enough the importance of organizations such as Aleanca LGBT or Pink Embassy during these circumstances. The film was produced within the context of a one-month artist residency organized by the former together with the Swedish Unstraight Museum and Swedish Institute as an attempt to work with art as a means to bring forward LGBTQ and human rights issues on the political agenda. These questions are some of the many concerns in Albania’s approach to becoming a member of the European union. Some critical voices describe it as “pink washing” and argue that a lack of grounding of the rapid changes in the society might backfire anytime soon, but you need to start somewhere?

Early on, the rich history of the Albanian film production intrigued me. In my practice I‘ve been interested in how existing narratives are being used, how these can be interpreted, and how one can search for representation and create identification – in this case, in a state controlled popular culture – and make the narratives one’s own, when nothing else is there. Lately there’s been a new interest in these films, and sort of a cult following resulting in screenings, festivals and so forth. The project initially started with a questionnaire mainly addressed to the elderly within the community, trying to collect a significant scene, film or character that could be understood as important for representation, in a process of forming an identity and/or a community. Koncert Në Vitin 1936 was one of two films that was presented to me and also received the most responses. As an artist, it’s quite conceited to come from the “outside” and make a critique after spending just a short period of time in this context, but the whole project tries to offer alternative readings on queer moments in a well known film – a shared part of history – that weren’t so visible before. It forms a dialogue between the three different periods in the modern history of Albania: monarchy, communism and the republic of the present.

Zare Trëntafile is a famous love song addressed to women, but the lyric, “How you cheated us, Oh Zare. How beautiful you are,” seems to provide other connotations as well. How do you look at this song?

In the original film the song itself functions as a catalyst that releases the political tensions when the two stubborn emancipated women finally are able to perform. Everyone bursts out in tears, and the song manages to unify the people in the small village. Zare, which is a feminine coded name, is also the Albanian word for “dice”. Nowadays Zare is slang used as a description for someone who is easily played with, mocked and bullied. Trëntafile refers to the flower rose. It can be read in so many ways, it’s a calling, to come out, join your loved one, join the community, join the struggle, and still it can be someone that somehow turns on you. Such a simple, yet powerful play with words.

What inspired you to make Lepurushja the subject of your film? Can you tell us more about Lepurushja?

When starting out, we actually did a small audition for the film. I already knew that I wanted everyone involved to be connected to Aleanca somehow, and the main protagonist should be a performer connected to the organization as well, a person who usually performs during Aleanca’s closed and secured community parties. Lepurushja was one of the young queers who uses the organization as a safe haven and usually hangs out in the backyard during the afternoons. It’s a quite diverse gathering of kids, some of them being homeless, sex workers, or part of the Roma minorities. Lepurushja just happened to be the first person I met besides the local organizers the day I arrived in Tirana. The name itself means “Bunny”, and became a persona, a heightened version of hirself.

The location you chose is also full of historical symbols. Can you tell us about the mausoleum Piramida and why you decided to film there?

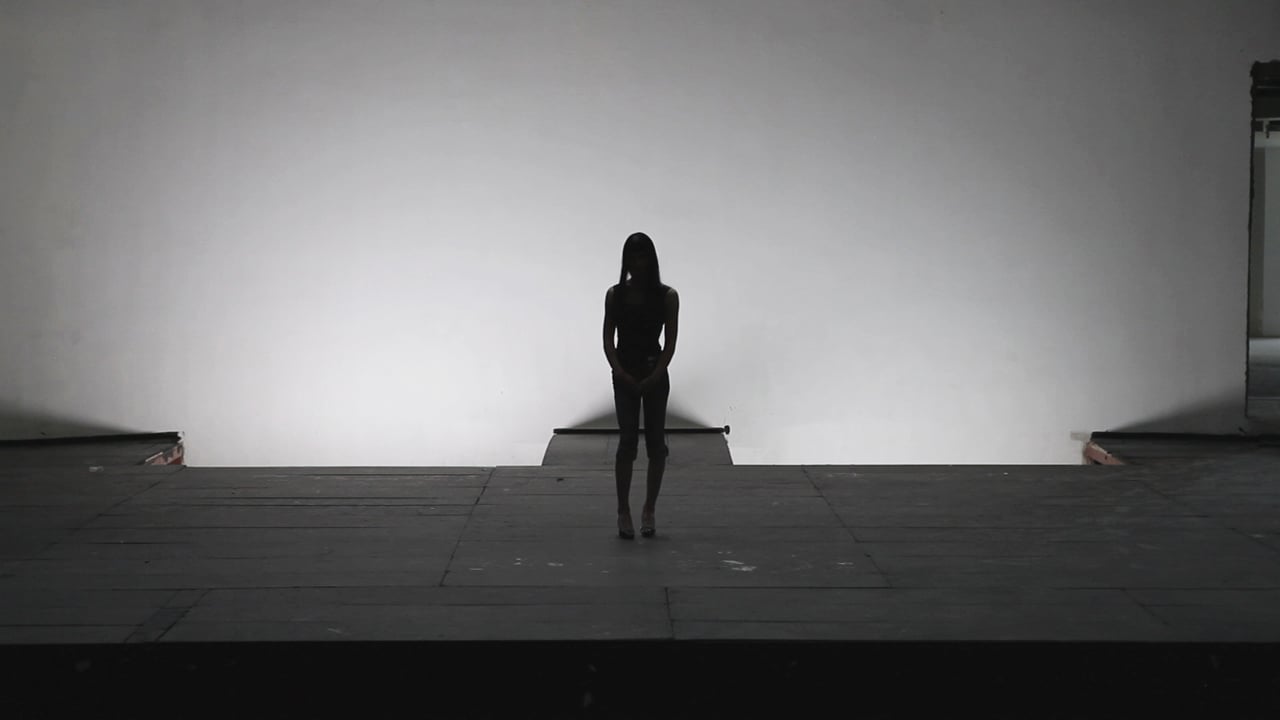

Piramida, by some described as a “mausoleum”, is a museum over the former dictator Enver Hoxha, initiated by his daughter in the late 1980s. Placed in the middle of the city, it functioned as a center for culture, but soon it became a symbol of political disagreements and historical revisionism and now exists under the constant threat of demolition. Filming there was a statement, to have an unwanted non-confirmative gendered body, a politicized subject sneak into the remains of totalitarian power structures and take this into hir possession. Lepurushja performs a simple traditional love song during a private moment in front of an empty stage. Lepurushja does not only represent hirself in this case, but becomes a serene voice of an unheard community. It is a political act.

Comments (0)